ON GARDENS & CIVILITY

concrete hellscapes, manufactured utopias, and too many / not enough questions

A few weeks ago, I decided to start a humble, makeshift garden. I’d been thinking about trying my hand at growing herbs, vegetables, and the odd flower for a while, and this year, I finally got around to it.

Part of my motivation for the project was wanting to add some greenery to an old concrete and stone yard. The other major factor was that I was getting tired of never finding any decent basil at the market—and basil is essential in my home. I rushed into buying planters then realized tomatoes were a no-go this year—my planters were too shallow. So, I started with the basil, and then added lavender and rosemary and mint to keep away pests, and then ventured off into marigolds and the like.

One morning, only three or four weeks into my journey, I woke up too early and couldn’t find sleep again. After rolling back and forth a few times, I filled my watering can and made my way to the yard. The early morning spared me from the sun, but the property owner was taking advantage of it too-completing his tasks for the day early. While making small talk and making my rounds, I discovered a white film on some of the mint leaves—so thick it looked like a splatter of latex paint.

You haven’t painted out here recently, have you? I asked, in a lower voice than usual.

No, he said, but I probably should paint soon.

Don’t worry, I laughed, I won’t mention it to your wife.

Please don’t, she’ll have painters here tonight if she hears of it.

I rushed inside to my apartment to ask the great internet my burning question. White film on mint leaves, I typed into the search engine. The search engine spit back, Mildew.

MILDEW! FUCK!

The one thing that was meant to protect all my other plants was sick and under attack.

***

I probably think about gardens more than the average person, and there are reasons for that.

Growing up, my grandmother kept a kopsht or bahçe, where I could pick strawberries and figs and cucumbers and oranges depending on the season. Nana’s bahçe is now in the middle of an overly developed, concretized neighborhood in Tirana, but it was once one of very few houses on the outskirts of the capital city where sheep and cows still grazed the fields around it.

There is a reason I do not immediately recoil when a bee approaches my neck. I was never raised to see them as a threat. Instead, I know them to be hard workers, pollinators, blessings.

There is a reason I don’t wear gloves when I dig through soil—I don’t see the dirt under my fingernails as dirty. I recognize it as part of the earth that I came from, as the work my ancestors did for centuries and centuries. As recently as one or two generations ago, my people lived with the land, not on it. When I was a child in Albania, there were still traces of this life all around us.

The grazing fields were still there when I left Albania for the Bronx, my first encounter with a mostly concrete city—and I think my first encounter with an indoor supermarket (you should have seen my face when I first entered a Costco). But even the Bronx used to be farmland. And even today, it is the greenest borough of New York City. And even in the Bronx, my mother found a way to get us back to nature.

Mami worked two to three jobs on weekdays to afford small pleasures like the then-astronomical admission fee for the New York Botanical Garden, only a short walk away from our new home. The inside of the gates, once a public park on Lenape lands, now has perfectly manicured lawns and curated foliage.

My relationship with the Garden grew as I got older. I became an environmental educator (unpaid) at the children’s garden situated within the gates. And more than fifteen years later, I returned to the Garden in a special events role during the Ebony G. Patterson exhibition—an exhibition by the Garden’s first artist-in-residence.

Patterson’s speech at that year’s spring gala was a call to reflection and interrogation: How are gardens part of a larger culture of colonization, a larger attempt to tame nature?

How are the things we view as unsightly guests or pests actually part of a larger ecology that serves a purpose in nature’s patterns and cycles?

Why do we treasure the short-lived bloom of a peony and look to immediately end the life of a weed?

Which species have we already lost to human carelessness or deliberate intervention?

These questions stuck with me throughout my time at the Garden and long after my departure, and nothing has prompted these questions more for me than keeping my own little garden.

When I first thought of keeping something alive in this little plot of concrete, the property owners mentioned they had once bought living plants for the yard, but they had died.

They’re a lot of work, you know, they’d say over and over again as if they were trying to convince me that the effort to keep something alive wasn’t quite worth it. The work required wasn’t even on my mind, to be honest. I found myself wondering if they’d say the same about a child or a dog—I’m sure they wouldn’t.

I’m not touching them, they’d remind me, as if the burden of beauty was something to be dreaded instead of treasured. I wondered why the research and care required to keep something green was such a disturbance to their lives—and not just them, but so many people.

When other people see nature swallowing up an abandoned building or pushing through a crack in the sidewalk, they’re stunned. It’s crazy how nature takes over, they say. The conversation tells me they believe humans are a necessary mediator between nature and its planet—like if we’re not here to cut things down, the whole earth will be swallowed in green.

I always wonder, sometimes out loud, Aren’t we the ones who have taken over? When I see nature swallowing up an abandoned building or pushing through a crack in the sidewalk, I’m stunned too.

I think, What an incredible, abundant, luscious living thing! I hope it thrives!

***

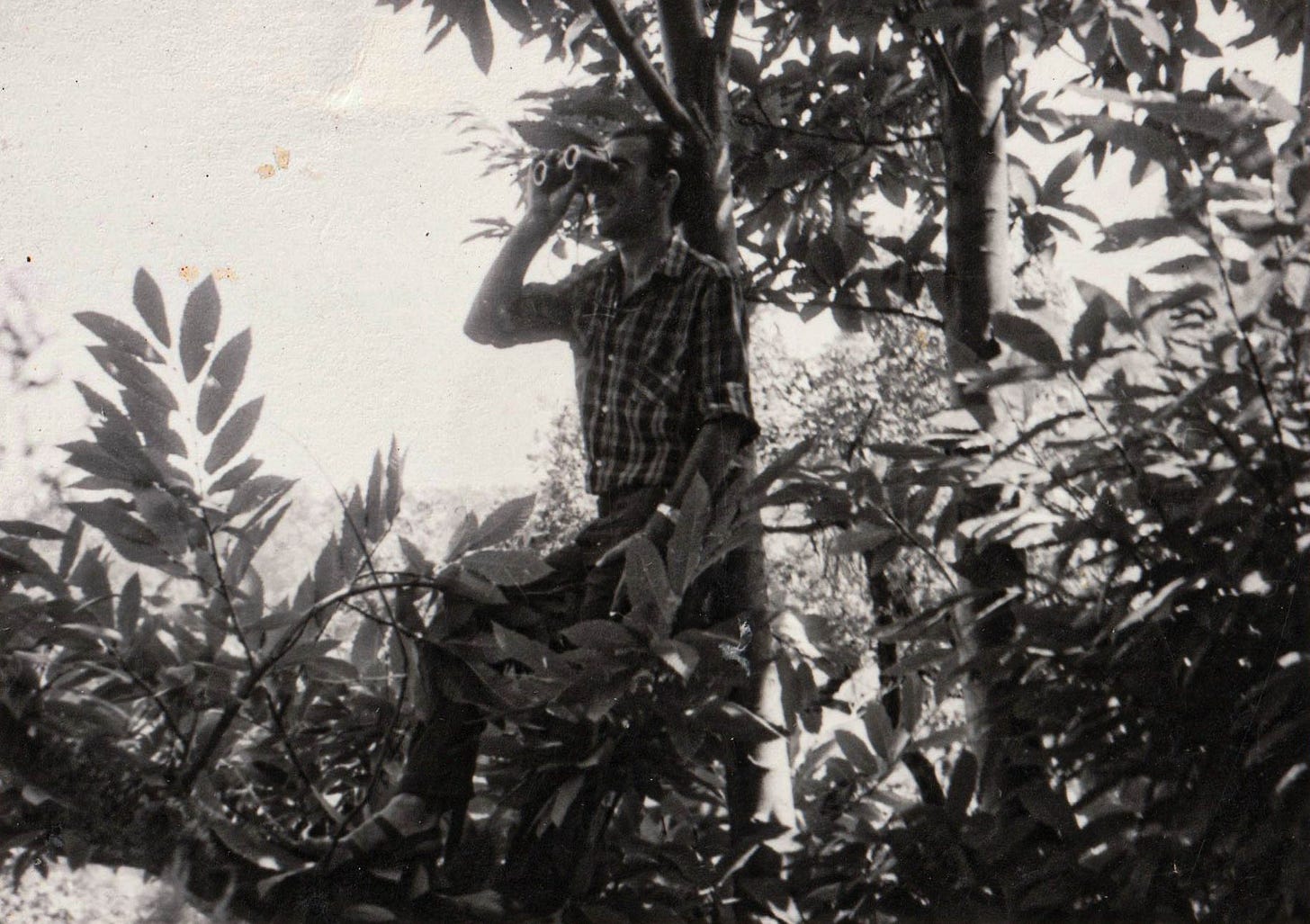

My grandparents grew up in the mountain villages of northern Albania, where the land boasts natural abundance and biodiversity. They came down those mountains when Albania’s Hoxha regime began industrializing the country. There are pictures of my grandfather climbing trees to set up the first electrical lines for my mother’s hometown of Laç. (This was a boy who bathed in a river and lived amongst the folktales of the deep woods.) And my grandmother became one of the first teachers in Laç. (This was a girl who carried water up and down mountains.)

My grandparents were crucial actors in the city-building efforts of their time, and in some ways, they believed this was part of creating a more civilized country—a perspective I might argue with them about today if they weren’t in their later aging years. In many ways, they had reasons for believing that this was progress: literacy rates sky-rocketed, people had work, factories were opening, institutions were forming, and important social services became available to them.

Village life was (and is) hard. But though they’ve now lived a city life for most of their lives, my grandparents never forgot about the land. Even when they moved to New York, their geraniums climbed the apartment window of their seventh-floor studio. My grandfather could pick a dying stem from anywhere in the Bronx and nurse it back to life in that tiny apartment.

Was this the key? Ancestral knowledge? Closeness to the practitioners of that ancestral knowledge? Roots in a country that industrialized later than most? Summer visits to your grandfather’s farmland, complete with homemade cheese from the family’s own sheep—sheep that grazed on the land they worked for generations?

If it was the key, I thought, many people I knew did not have it.

Even I was barely holding on. Overstimulated after twenty-five years in New York City, I make calls to my grandfather from the top of a dune in Colorado or a cliffside in Ireland. I make the same joke every time, O Babuç, it’s so funny, isn’t it? You all worked so hard to leave the village and come down the mountains, and here I am, living in the biggest city in the world, and all I want to do is return to the mountain.

Having the memory—ancestral or personal—kept me connected to the desire. But the memories were closer for me than they might be for most people. So could I really blame them for their lack of effort or affection towards living, green things? If they had never experienced those mountain fields, could I fault them for not marveling at the spontaneous spring bloom of daffodils along the highway? Could I ask these people to appreciate anything other than a manipulated flowerbed or a well-maintained (terrible-for-the-fucking-environment) lawn?

When I think about this—how our frameworks shape our interactions with the world, how exposure or lack of exposure shapes those frameworks—I’m able to conjure up empathy and understanding for people who feel so differently than I do, who don’t marvel at the small miracles of nature all around them.

Still, bigger questions rise to the surface.

In a world that is increasingly overdeveloping land, stripping it of its natural resources, and laying concrete wherever possible, is it true that civilization has arrived?

Are strip malls and oil drilling and convenience the pillar of society?

In a world where an island can be bought and sold for the purpose of luxury resorts, is it true that civilization has arrived—at least for the wealthy few who seek to exploit its pleasures? Do manufactured utopias for the top 1% make us feel like we’ve finally figured it out? And who has the right to land in this reality?

When we remove ourselves from the natural world, from the patterns and ecologies that have always nurtured us, do we become more civilized?

And really what I am asking here is: When we set our ambitions on creating civilization, do we create civility? Do we promote humanity? Or is civilization something else entirely?

Is the pursuit of civilization what allows us to commit heinous acts—against each other, against the earth?

Is the pursuit of land, ownership, and nation-making what allows us to use the earth as a weapon—to coordinate and weaponize starvation against entire populations?

Does our treatment of weeds or the smallest of creatures reveal something larger about the way we value life? About how easily we justify genocide? About the euphemisms we assign to what can only be described as organized and deliberate extermination? About what we’re willing to kill for our own comfort?

If we label a thing a pest . . . If we find a way to deem it a nuisance . . . Is that how we justify our own violence?

And if we do it in small ways all the time, can we really be surprised at the large-scale volatility we face globally today?

***

I realize I have only offered you questions. But the interesting thing about questions is that they give you much more than they ask of you—if you’re listening. They can be daunting, but they can open things up too, lead you down paths of wonder that weren’t visible to you before.

The morning after I wrote these questions down—these big questions about humanity and civilization and the ripple effect of our smallest actions—I went back to my humble garden.

I didn’t tell you this earlier, but the marigolds I planted had all dried up in the heatwave a week or two ago. I had to learn how to prune them, and each stem I cut felt like a beheading.

The reason I planted the marigolds in the first place is also tied to loss in some ways. When I was a toddler, I remember the full marigold blooms at my tiny feet as I balanced myself on the stone-framed flowerbeds of Tirana’s city center. This scene is two redesigns, demolitions, and reconstructions ago.

It is both strange and not strange to me that the morning after I wrote these questions down—the morning after I asked myself to pay more attention—a new marigold bloom appeared in my yard.

Maybe that is the answer I can offer. Taking the time. Offering careful attention. Engaging just enough to ask the questions and sit with them.